French hallmarks on silver appeared already at the dawn of the Middle Ages, but a unified marking system was formed in the country very late. Early French hallmarks are quite difficult to identify due to confusing rules that changed several times. A unified standard was approved only in the 19th century, and since that time the origin of the product can be determined without any difficulty.

English silver standard.

So, English silver hallmarks. English standard. The brand is a walking lion. The English silver standard - 925 standard - appeared earlier than all others in Europe and has survived to this day. The branding system developed from 1300 and was finally established by the middle of the 17th century.

Each British-made product has a standard set of marks: the British Standard mark, the city of manufacture, the annual mark and the maker's mark. If a piece has fewer than four hallmarks, it is either made in another country or is not silver. Until the end of the era of Queen Victoria, a fifth mark was placed, which meant payment of tax on the product in favor of the state. Commemorative stamps are still placed on anniversaries.

The most common British standard mark is the walking lion. This mark confirms that the product is made of 925 sterling silver. It appears on all products tested in England. This mark is also placed on items from other countries imported into England.

The origins of the branding system in France

French hallmarks have no less ancient history than their British counterparts. The difference is that in England the tradition of marking metal according to uniform rules appeared very early, and compliance with established standards was strictly controlled. French jewelers have long branded their products with the label maison commune, meaning the commune where the workshop was located. Every city had its own symbol, of which there were already many in the country at that time.

Until the 13th century, French marks were applied to all elements of the product, and each part had its own identification mark - for example, the base of a jug and its handle could be marked differently. The first attempt to bring order to the rules of branding was made by Philippe II de Valois le Hardi. In 1275, the monarch issued a decree requiring goldsmiths to put a workshop stamp on silver. The sign was supposed to be placed inside an equilateral rhombus.

In the next century, state regulation of jewelry was seriously complicated by the fragmentation of the country and the protracted war with England. By the end of the 15th century, the disparate territories were finally united, the power of the monarch was strengthened, and the ensuing peace contributed to the development of crafts. France dominated the European market and supplied luxury goods to every country in the world. Jewelry manufactories appeared, which began producing silverware, jewelry and trinkets.

Henry III of Valois (Henri III de Valois) ascended the throne in the midst of religious wars, which significantly depleted the treasury. In 1577, the monarch, in need of funds, tried to impose a tribute on jewelers and approved a new mark, which indicated payment of the tax. Since the treasury received income from renting stamps to tax farmers, two years later Henry decided to introduce several additional stamps, but encountered resistance from Parisian jewelers, who simply refused to carry out the king’s next decree.

British Standard Hallmarks

There were five British hallmarks in total: A - 925 silver, England; B - 958 silver (set in 1697-1720);

C – 925 sterling silver, Glazko; D - 925 sterling silver, Edinburgh; E - 925 silver, Dublin.

Another mandatory mark is the mark of the city of production. The mark of the city of production. London. The photo on the right shows the London city hallmark. From 1478 to 1822, the leopard wore a crown on its head. From 1822 to the present day, the mark has retained the appearance that you see. Each city has its own mark, which can be found in the article City marks of the United Kingdom: England, Ireland, Scotland.

An important mark is annual. It was first presented in London in 1478. From this time on, annual marks were never repeated. They represent twenty letters of the Latin alphabet. Every twenty years the font of the letters, the register and the shape of the shield in which the letters are inscribed change. An example of such a mark in the photo below is the letter “u”, which corresponds to 1875. You can learn more about annual stamps in the article English annual stamps.

Annual and tax stamps

The evolution of the assay system in France

The next dramatic changes in the assay business occurred during the reign of Louis XIV. In 1672, the king introduced a new tax on the right to mark gold and silver. The right to collect it was received by tax farmers who certified the payment of tax payments with a special stamp. In 1681, the rules became more complex, and branding began to be practiced at every stage of production. In practice it looked like this:

- The jeweler applied personal markings to all details of the item before it was installed.

- Then the master provided the parts to the tax farmer’s service, where a stamp was placed on each one, indicating mandatory duty.

- Before the final assembly of the item, the sample of each element was checked and the mark of the city was placed on them.

- At the final stage, the craftsman assembled the product, paid a fee, after which the farmer affixed a confirmation stamp. Only after this the item went on sale.

The final labeling varied depending on the tax district, of which there were more than a thousand, and some of them are still not systematized. When changing tax farmers, the new tax collector could use the stamp of his predecessor or order a new one. However, in this case, he branded the silver again, which he made an entry in the account book.

The symbols of the communes were varied. In Reni and Rouen, stylized letters topped with a crown were used, in Toulouse - monograms and coats of arms, in La Rochelle - images of animals. Dates and tax marks were indicated by letters and, in rare cases, by numbers. By the signs one could easily identify the tax farmer.

The French assay rules of this period were rightfully considered the most complex in Europe. Historians attribute this fact to the widespread belief that precious metals could be obtained through alchemical means, and a long chain of marks served as a guarantee of authenticity for buyers. The masters were not bothered by multi-stage control: the demand for French silver was high, and the costs simply increased the final cost of the product.

Maker's mark on English silverware.

Another mark that is placed on all products is the manufacturer’s mark. This branding became widely used in 1363 in London. First of all, the introduction of the mark was supposed to help establish the manufacturer’s responsibility for the manufacture of products of inadequate quality and standard. Until the 17th century, stamps in the form of pictures - pictograms - were mainly used for this purpose. But from the beginning of the 17th century, it became common practice to use the initials of the master or owner of the company for the brand.

In the photo on the right is the mark of the largest London company - Garrard and Co LTD. The company traces its history back to 1722 until the present day. During its existence, it was a supplier of silver to the royal court of six monarchs. Recognizing a master's mark is the most difficult stage if the master is little known. To do this, you need to use special catalogs with examples of stamps.

Hallmarks and hallmarks of silver

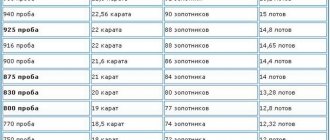

The most popular and widespread silver alloys are 875 and 925. They are used to make decorations and tableware items for table settings.

For tableware and some types of jewelry decorated with enamel, it is customary to use an alloy of 916 standard, and an infrequent 960 standard is used for the manufacture of filigree products.

When coating silver or brass (rarely copper) products to improve the decorative component and, of course, to protect against rapid oxidation and deterioration, they are electrolytically coated with a thin layer of 999-carat silver.

I recommend that you don’t bother and don’t go into the details of branding if you’re just thinking of buying some trinket that’s cheaper than a book about stamps. Buy it and be happy, if you like it, wear it for your health! If you seriously and systematically decide to spend part of the budget or freed-up funds on the purchase of silver items, then, of course, start with the purchase of special literature. No amount of online excerpts can replace the printed edition of a respected author.

I am adding a photo answer to a frequently asked question about the hallmarking of gold and silver items imported into and exported from Russia at the turn of the 19th – 20th centuries, namely in 1899 – 1908. These are excerpts from two books by very serious and authoritative experts. V.V. Skurlov and A.N. Ivanov “Marking of Russian gold and silver items at the turn of the 19th – 20th centuries” Collection of archival materials. Here are some chapters:

- Report by S.Yu Witte and V.V. Kovalevsky According to the draft assay regulations...

- Correspondence between goldsmith Otto Both and officials of the Ministry of Finance

- About alloying coins for making gold products

- About the detention of products of the Faberge company traveling salesman Arthur Beaux in Baku in 1901

- Documents on the introduction of hallmarks of the 1899... 1908 model

- Inspections of Moscow jewelers by officials of the Assay District in 1907

- About the quality of the new hallmarks of the 1908 model

- On the sale of gold items with false hallmarks to the French goldsmith Ferro

- About counterfeiting of hallmarks

- Abuses by jewelers

- Secret assay tent

- On the examination of marks at the Mint

- On the examination of stamps using microphotography

- G.Ch. Bainbridge “The Hallmarks of Faberge”

- F. Birbaum “Assay tents and jewelry art”

- K.A. Snowman “Stamps on gold items and names of masters”

Appendix: Rules for hallmarking gold and silver products of 1899 and 1908 and the second photo of Akkalaev R.Kh. Assay marks of Russia and foreign countries. Reference and methodological manual on branding products made of precious metals. Both books are wonderful, very useful! If you decide to get into Russian jewelry or collecting antique silver, you simply need them, I highly recommend them. Definitely buy it. Akkalaeva can still be found, it is being republished, it is quite inexpensive, but the first book is no longer on sale. Decide for yourself, click on the photo, it will open in a large expansion.

Russian stamps 1899 - 1908 for imported and exported products Skurlov Ivanov Akkalaeva

French stamps and hallmarks of silver, gold, platinum.

Jewelry made from precious metals is branded to:

- identify the manufacturer's factory,

- find out the sample and quality of the precious metal from which the product is made.

| The dog's head was placed both on products intended for the domestic market and for export Pt 950 samples. |

| Head of a young girl For legal products for export Pt 950 |

| Mascaron 1 For products imported from treaty countries Pt 950 standard. |

| Mascaron 2 For imported products sold in non-treaty countries or at auctions Pt 950. |

| Special gold hallmarks |

| Eagle head 1 Mark for a gold product (crucible Au 920 and tested by cupellation) |

| Eagle head 2 is the same, but for 840 gold |

| Eagle head 3 for Au 750 gold |

| Eagle head 4 Hallmark for gold Au 750, tested on touchstone |

| Rhinoceros 1 Identification badge of Paris, appears with a weight combination stamp, for 750 gold |

| Rhinoceros 2 Departmental ID badge, appears with a weight combination stamp, for 750 gold |

| Flea? Certificate mark for imported items made of 18-carat gold into France. |

| Head of Mercury 1 For hallmarking of exported gold products Au 920 gold. |

| Head of Mercury 2 For hallmarking of exported gold products Au 840 gold. |

| Head of Mercury 3 For hallmarking of exported gold products Au 750 gold. |

| Head of Mercury 4 Likewise |

| Owl Hallmark for imported (not found in France) gold goods Au750 fine gold |

| Egyptian head. 1 The mark was placed by virtue of the law of January 25, 1884 on watch cases 4th and exclusively for exported ones. |

| Egyptian head. 2 The mark was placed by virtue of the law of January 25, 1884 on watch cases 4th and exclusively for exported ones. |

| The export stamp must be attached to the Head of Egypt stamps. 1 and 2. |

| Movement of watches According to the law of 1892, it was set when paying customs duties at the border. |

| Special hallmarks for silver items. |

| Head of Minerva 1 Hallmark on a French item tested by cupellation silver Ag 950 |

| Head of Minerva 2 Mark on a French product tested by cupellation silver Ag 800 |

| Boar's head Mark on a French product, tested on a touchstone Ag 800 silver Paris |

| Crab Mark on a French product, tested on a touchstone silver Ag 800 – departments |

| Flea? Hallmark for imported silver products similar to French Ag 800 silver |

| Swan Placed on imported silver and on watches, corresponds to Ag 800 silver standard |

| Head of Mercury 1 Hallmark for exported silver products corresponds to Ag 950 silver standard |

| Head of Mercury 2 Hallmark for products manufactured for export corresponds to Ag 800 silver standard |

| Head of Mercury 3 Hallmark for exported silver products corresponds to Ag 800 silver standard |

| Dove (watch details) Confirms the fact of payment of duties at customs. |

| Joint hallmarks for gold and silver items. |

| Hallmark ET (Paris) For art, auction sales and unidentified items. |

| ET stamp (departments)same meaning for departments |

| Head of a hare (rabbit) Items exempt from duty were marked. |

| Flea Ancient stamp (1864) |

| Head of an eagle and a boar For French products (proportion 3 to 100?) |

| Identification stamp For objects of gold and money (small parts of watches) temporarily imported into France, duty-free import |

Source: antik-invest.ru

If you find an error or typo, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter.

0 0 votes

Article rating

Complete set of English hallmarks

The photo on the left shows a complete set of marks from the item that served as the sample for this article.

So, in order to determine the origin of an item you need to:

- Find one of the British Standard marks (there were 5 marks in total).

- Find the city's stamp.

- After you have found the city stamp, check the annual stamp. The system of annual stamps is different in each city.

- Then, by the manufacturer's mark, you can find out which company the item was made by.

Early English silver

Despite the abundance of information about the English hallmark system, very few items from the early period have survived. It is known that dishes were made from silver, but in case of any damage or severe wear, the item was immediately sent for melting down. Every noble Briton had his own silver spoon, which he took with him on his travels. The church ordered communion cups from jewelers, which were made from a single piece of sheet metal and polished with pumice.

The progress of silversmithing was hampered by a shortage of raw materials, which in the 15th century became a big problem for the economies of European countries. In those days, jewelers worked more with gold because it was easier to get. The plague epidemic significantly reduced the population, which caused difficulties in transporting ingots from the East. The problem was partly solved by the opening of new mines in Saxony and Tyrol, and in 1471 Italy was included in the list of main suppliers of silver.

Jewelry art reached its true flowering during the Tudor era. Queen Elizabeth I greatly valued extravagant silverware, which was customary in that era to be plated with gold. Craftsmen melted gold and mixed it with mercury, and then applied the composition to the surface of the object and fired it. When heated, the mercury evaporated, and the coating was firmly connected to the silver. The process was unsafe for both the jeweler and the owner of the dishes.

During the heyday of the Renaissance, English jewelry was strongly influenced by German, Italian and Dutch craftsmen, which was reflected in the decoration of products. The dishes were decorated with engraving and chasing, and floral ornaments came to the fore. However, in 1603, Elizabeth was replaced on the throne by the Puritan James I, who was an ardent opponent of luxury. During his reign, gilding of silver almost ceased, and preference was given to simple lines and smooth forms.

British silver in the 18th century

After the decline caused by the revolution, a period of restoration began. During the reign of Charles II, the style of masters from Holland and France, which was popular among the English nobility, became widespread. Vases, jugs and toiletries were decorated with lush baroque ornaments with an abundance of acanthus, flowers and figures, characteristic of the engravings of Dutch artists. Forms borrowed from Chinese porcelain came into fashion, which was caused by the active activities of the East India Company.

The coming to power of the Puritan William of Orange (William III) again returned the manner of work of artisans to simplicity. The trend has gone down in history as the Queen Anne style, which is characterized by simple, noble lines, restrained proportions and sleek finishes. Two-handed cups and specially shaped mugs, traditional for the British, remained popular and remained in demand over the next two centuries.

The massive influx of Huguenot craftsmen from France in the 18th century led to the appearance of new pieces of tableware with elegant and luxurious decoration - plademénages, gravy boats, terines, spice vessels. Rococo decorative techniques with rocailles, flowers and marine elements revealed all the plastic possibilities of silver. One of the striking manifestations of the style is the chinoiserie movement, which developed under the influence of Chinese exoticism.

Beginning in the 1770s, neoclassical style replaced Rococo. Massive wine fountains and bulky splashes gradually replaced light transfers, oval jugs, and various decanters. Lush jewelry went out of fashion, and jewelers focused on making entire ensembles of dishes made in the same style. The main role in the decoration was played by discreet decor, inspired by ancient architecture.

The products of Rundell, Bridge & Rundell, the largest jewelry manufacturer at that time, are widely known. The innovative techniques of the company's craftsmen largely determined the development of silversmithing in the era of Queen Victoria. The owners of the company were the first to open an art studio, where projects were created based on the work of the masters of Gothic and Mannerism.

Victorian silver

At the beginning of the 19th century, another major silver manufacturer appeared, which made a great contribution to the formation of the Victorian style. The company's artists partially repeated the forms of table decorations of the previous century, but at the same time significantly expanded their range. Award cups, memorable prizes, gift items in the form of bowls, unusual vases, urns, and sculptural compositions appeared. British products were distinguished by deep symbolic and semantic content. During the time of Queen Victoria, there was a widespread tendency to present silver awards for military exploits, achievements in sports, and success in the field of charity, which caused a flow of orders for things in the national style.

In 1830, the company of James and Sebastian Garrad received the title of suppliers to the royal court. The brothers invited sculptor Edward Cotterill, an adherent of the naturalistic style, to the position of project developer. The master’s works played a big role in the promotion of the company and were noted at the World Exhibition of 1871.

Great Britain's silver was highly valued both abroad and within the country. The development of industry and the reduction in cost of production of mass products led to the fact that even families with average incomes could afford precious tableware. Silver sets served as a sign of wealth and were passed on to subsequent generations. With the advent of more practical materials, the popularity of silver gradually faded, but at antique auctions the products of English craftsmen are in high demand.