Greetings, dear visitors of our website! Today's topic comes to us from the middle of the 19th century, but remains relevant and hotly discussed today. Once upon a time, the introduction of the metallic gold ruble into internal monetary circulation made it possible to raise external market relations and confidence in the ruble among foreign industrialists to a qualitatively new level. The Russian currency, along with the British pound, has become the most stable in Europe. I propose to find out what the gold ruble is and what role the gold standard can play at the present time.

What it is

The coin ruble made of gold is a metal monetary unit of the Russian Empire introduced into circulation in 1897.

Imperials and semi-imperials were in circulation in Russia along with silver metal money and paper credit notes since 1843, but were used more often as a special currency for foreign trade. Only after the reform of Count Sergei Witte was gold introduced into internal circulation in the country.

A Brief History of the Introduction of the Gold Standard in the Russian Empire

In the middle of the 19th century. The Russian Empire had a bimetallic monetary system. The royal treasury contained equal amounts of silver and gold. But the paper ruble was more tied to silver.

As a result of the crisis that followed the Crimean War in 1858, credit notes lost their security - the state treasury stopped exchanging them for metal coins. It became clear that bimetallism with a tendency towards silver monometallism could not continue to exist, and by the end of the 19th century. monetary reform is overdue.

The Minister of Finance of the Russian Empire, Sergei Witte, having analyzed the single currency system of the leading industrial countries, placed a bet on gold. And I was not mistaken. The introduction of precious coins into internal monetary circulation gave the country the necessary economic stability. The rapid growth of industrial production in pre-war Russia and the more than doubling of the empire's gold reserves provided the Russian ruble with a stable footing.

Such a system in Russia existed until the beginning of the military mobilization of the districts bordering Austria-Hungary, when more than half a billion gold rubles suddenly disappeared from circulation, sinking into the numerous hiding places of ordinary people.

Gold ruble in Soviet Russia

In 1922, the People's Commissar began minting Soviet chervonets of 900 standard, which again stabilized the ruble exchange rate. The content of pure gold in one chervonets is 7.74234 g.

Sergei Yulievich Witte

Sergei Yulievich owes his unusual surname Witte to his paternal family line, which came from Germans living in the Baltic states. But on his mother’s side he is Russian. In the family of his mother (daughter of the Saratov governor) there are such famous personalities as Major General Prince P.V. Dolgorukov and memoirist E.A. Sushkova. Upon marriage, Julius-Christoph-Heinrich-Georg Witte converted to Orthodoxy and changed his name to Julius Fedorovich.

Sergei spent his childhood and adolescence on the outskirts of the empire, first in Tiflis, then in Chisinau. After completing his studies in Odessa, where the family moved after the death of his father, Witte was offered a professorship. However, relatives opposed this, and Sergei Yulievich begins climbing the career ladder from the position of a specialist in the operation of railways in Odessa. Over time, he headed the operation service of the Odessa Railway, and after moving to St. Petersburg he became the head of the operational department of the South-Western Railways. When transferred to Kyiv, Witte meets the Warsaw banker Blioch and professor Vyshegradsky. Both of them had a strong influence on the future fate of Sergei Yulievich. The publication of the book Principles of Railway Tariffs for the Transportation of Freight reveals Witte’s talent not only as a progressive railway worker, but also as an experienced economist.

In the mid-80s of the 19th century, Sergei Yulievich became the manager of the Southwestern Railways and met Emperor Alexander III. From February to August 1892, Witte held the position of Minister of Railways. It seemed that you could do it in six months? But Witte, firstly, is carrying out a reform of railway tariffs, and, secondly, solving the problem of the accumulation of a large amount of untransported cargo, which they could not cope with before. Such successful activity does not go unnoticed, and Witte receives the post of Minister of Finance, where he will serve for 11 years. In addition to monetary reform, the main milestones in this position for Witte were the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway, a profitable trade agreement with Germany, the introduction of a wine monopoly and negotiations with China, which resulted in the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway.

Reasons for canceling chervonets

At various points in history, most often during a crisis, precious metal coins had to be temporarily withdrawn from circulation. Securing money with gold has many advantages, among which the main ones are high density, small storage volume, stability, uniqueness and other qualitative characteristics of the precious metal.

However, later gold coins had to be abandoned completely for a number of reasons:

- Chervonets of high standard had increased softness, were easily scratched, and deteriorated when frequently checked for authenticity by biting. Coins were often lost, which upset the balance of free circulation of money.

- The rapid growth of trade turnover could no longer be ensured by minting coins in the required volume.

- The large weight and small volume are convenient for storage, but caused a number of inconveniences during transportation. Even a small purse of gold was extremely weighty.

This led to gold being kept in the treasury, and paper money becoming a kind of certificate for it. After the abolition of the standard in the United States (1971), almost all countries abandoned their currency peg to gold.

Gold Russes (1895) and proof coins (1896)

Along with the development of new money, they planned to change the name of the monetary unit. The options were varied. By analogy with the Bulgarian lev, the ruble could be replaced by the eagle currency. The usual imperial could remain as a name, but without translation into a ruble analogue. Admiring the fact that France has the franc as its national currency, Witte proposed abandoning the ruble in favor of the Russian currency. Replacing rubles with russ would retouch the upcoming loss of the ruble by a third. New denominations, coupled with a new monetary unit, would not look as surprising as the fact that gold imperials, retaining the same weight, became 15 rubles.

In 1895, the St. Petersburg Mint received an order to produce five sets of russ in denominations of imperial (15 russ), 2/3 imperial (10 russ) and 1/3 imperial (5 russ). Standard 900-carat gold was used to make russians. 15 russ weighed 12.9 grams (11.61 grams of pure metal) with a diameter of 24.5 mm. 10 Rus were a third lighter, weighing 8.6 grams (7.74 grams of pure metal) with a diameter of 21.4 mm. 5 Rus had a mass of 4.3 grams (3.87 grams of pure metal) with a diameter of 19.6 mm. For now we decided to leave the edge smooth. Test coins were presented to the emperor, but they did not receive the highest approval. This ended the experiments to replace the ruble with a more patriotic monetary unit.

The sets have now become a historical and numismatic monument. Two of them remained on Russian territory, being on display at the State Historical Museum and the Hermitage. The huge numismatic collection of the Smithsonian Institution Museum (USA) boasts a third set. Another set is in a private collection. The coins of the fifth set were auctioned individually and were purchased by three private collectors.

The story with samples dating back to 1896 looks much more mysterious. As before, their main metal remained gold (90%), and copper served as the alloy (10%). However, the weight was correlated with the face value not according to the new standards, but according to the Rules on the Coin System of 1885. That is, the gold five-ruble piece had a total weight of 1 spool of 49.2 shares (6.45 grams), and there was 1 spool of 34.68 shares (5.81 grams) of pure metal in it with a coin diameter of 21.3 mm. The ten-ruble note was the standard imperial of previous years weighing 12.9 grams (pure gold - 11.61 grams) with a diameter of 24.6 mm.

What is the backing of the Russian ruble today?

Although Russia has been steadily accumulating the country's gold reserves over the past decade, these reserves are not enough to fully back the ruble. The factors that support the current ruble are foreign currencies, mostly the US dollar, and energy resources.

However, in conditions of economic pressure from OPEC, Russia needs alternative solutions.

Is the ruble currently pegged to gold?

Today's ruble is not tied to gold; the country's reserves in precious metals, in all its magnitude, can barely cover 5% of convertible currency.

However, recent discoveries by chemists in gold mining have significantly reduced the cost of extracting gold from ore, which can significantly accelerate the build-up of the country's reserves.

Rare Russian hundred francs

Collectors are interested in rare gold coins with a non-standard denomination of 37.5 rubles, which are called “Russian hundred francs”.

They were released in 1902 in a very small edition - only 225 pieces. Today, historians and numismatists do not have a common opinion regarding the purpose of these coins, because they have never been in wide circulation. There are three versions regarding their purpose:

- economic;

- award;

- gambling.

Some researchers believe that the unusual gold hundred francs were released in a small batch for testing. In the future, they were planned to be widely used for transstate transactions between the Russian Empire and France. This period coincided with the heyday of close cooperation between the two states in the Far East. But the money did not enter circulation.

The second version, which inspires more confidence, is this: rare rubles could be used as rewards or collectibles. They were expected to be distributed among the upper class as expensive gifts for guests. This version is supported by the fact that two hundred of the minted gold coins were given to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. And the remaining 25 pieces were received as a gift by Prince Georgy Mikhailovich. In 1903, ten more coins dating from 1902 were issued, which were solemnly presented to Prince Vladimir Alexandrovich.

In 1904, the last, 236th gold coin with a face value of 37.5 rubles was minted, especially for the Hermitage collection.

According to the third version, such coins could be used to play in a casino. But this hypothesis does not have serious confirmation.

Pros and cons of the gold standard

One of the main advantages of the gold standard is the almost complete absence of inflation. The Central Bank of the Russian Federation is taking desperate measures to protect the ruble in the face of European sanctions. Such collateral could significantly strengthen the ruble. Therefore, options for reducing dependence on the dollar are widely discussed in government circles, but there are many pitfalls.

Disadvantages of such a system:

- Gold has no fixed value. Its value is determined by the presence of supply/demand. Despite all the calculations of experts, it is difficult to predict the true reserves of gold in the earth's crust and the cost of mining methods that may be discovered in the future.

- The constant need to accumulate money supply requires a correlational growth of the gold fund, which is also possible only up to certain limits.

- In case of crises, there is a need to issue an unsupported volume of foreign currency.

- The complexity of internal macroeconomic transformations.

- Lending to individuals and legal entities will be limited.

- Problems in making international payments.

About the gold standard in Russia. Witte's gold.

Home » Real story » About the gold standard in Russia. Witte's gold.

Real story

Barkun 11/23/2020 1503

19

in Favoritesin Favoritesfrom Favorites 4

“The intrinsic or exchange value of money is determined, in essence, by the value of the metal it contains. The experience of all countries and peoples has fully and indisputably proven that no general agreement of state power is capable of giving money for any length of time a value higher than that which it has as metal ingots or, in other words, as a commodity.”

S.Yu. Witte.

“Even though the gold metal does not have all the theoretical advantages of an artificially regulated monetary unit, all quackery is excluded here and in practice it has proven to be reliable.”

Lord Keynes.

Start here, here, here. And here.

The mechanism for balancing the balance of payments through prices and the flow of metallic money, which underlies gold monometallism, was discovered in 1752 by the Scottish philosopher David Hume, whose name he later received. The bottom line: if a country has a positive balance in world trade, then gold comes into the country, which ultimately leads to an increase in prices due to an increase in money supply. This encourages the population to purchase cheaper imported goods, which leads to a change in the balance and gold begins to leave the country. At the global level, the supply of money is determined by the supply of gold. The discovery of deposits, changes in production technology, and military indemnities as a result of victorious wars lead first to an increase in the money supply, and then to an increase in prices and GDP. Reducing supply has the opposite effect, namely a fall in prices and GDP. But due to the limited gold reserves and the growth of global prosperity, this mechanism is becoming more and more inertial. As a result, in practice it was not prices and wages that fluctuated, but unemployment and GDP. Hume's mechanism is complemented by the mechanism of short-term capital overflow: a balance of payments deficit causes a reduction in money supply and an increase in bank lending rates, the increase of which attracts capital into the country. Those. the movement of capital begins to be determined by the differentiation of interest rates, which means that banking systems are becoming increasingly important, which have taken on the burden of equalizing the balance of payments.

The rarest chervonets is minted in 1906. The cost of a gold chervonets from 1906 is 200-250 thousand dollars. Only 10 of them were minted (and 20 five-ruble coins) at the St. Petersburg coinage, on the occasion of the anniversary of the coronation of Nicholas, as gifts to the grand dukes and ministers. Edge - indicating the contents. The Historical Museum has 2 such coins, complete with five-ruble coins, and the Hermitage has the same two sets. The rest scattered around the world...

At the end of the 19th century, within the framework of the gold bloc, the core (Great Britain, Germany, France, USA) and the periphery (Scandinavia, Southern and Eastern Europe, Russia, Asia, Central and South America) were formed, and the trade turnover between the periphery and the core accounted for more than 2 /3 of the total trade turnover of the bloc, only 1/3 is accounted for by core-core and periphery-periphery trade turnover. Due to the fact that the supply of gold is always limited, and the growth of welfare has an unlimited tendency to grow, gold monometallism in the long term always leads to deflation (and, therefore, a slowdown in GDP growth), especially in peripheral countries that do not have sufficient mechanisms to influence golden streams. Those. The lower the level of economic development of a country when entering the golden bloc, the lower, ultimately, the comparative (with core countries) pace of its real industrial development.

The prerequisites for understanding all of the above arose at the end of the 19th century, which means that before Yu.S. Witte’s task was not just monetary reform, but a comprehensive change in the state’s economy, in which he relied on the experience of his predecessors and associates. The possibility of a massive outflow of metal from circulation into “bags” within the country or abroad as a result of unequal trade turnover, the lack of gold reserves for free exchange, the threat of depreciation - all this was perceived as a very real danger. It is all the more real because there were simply no levers of influence on the process without increasing the role of industrial production and strengthening the state banking system. Not everything turned out as expected.

In general, the theoretical justification and practical preparation for the introduction of the standard were completed by 1895. But it still remained to convince the Emperor, the State Council and public opinion.

In the first years of Nicholas's reign, Finance Minister Witte tried to radically change the name of the Russian currency. By analogy with the French francs, they chose the name “Rus”. However, this word is not on the coins of 10 and 5 russ, instead of it there is the inscription “2/3 IMPERIAL”, “1/3 IMPERIAL” on the reverse. The edge is smooth. On the obverse is a portrait of Nicholas. Five sets were made per sample, but then this idea was abandoned. The cost of the set is on average 400 thousand dollars (set - 15, 10 and 5 russ). But only two can come to market, having gone into personal collections. The other three are in the Russian Historical Museum, the Hermitage and the American Smithsonian Museum.

In relation to the reform, society falls into three camps: conservatives (most likely “against”, but there are nuances), liberals (most likely “for”, but there are nuances), financiers (definitely “for”).

Conservatives advocate worldwide support for agriculture to the detriment of industrial and railway construction, they are represented by large landowners, and their positions are strong in the State Council. From their point of view, the introduction of a solid ruble reduces the export potential of Russian raw materials and bread.

Liberals note that gold itself is good, but there are no economic conditions for reform (low purchasing levels of the population, a passive trade balance of the country, a huge external public debt and the potential for its growth). In general, the same as now, it’s just that conservatives adhere to the latter position, and liberal monetarists adhere to the first.

The most active defenders of the introduction of gold monometallism were high-ranking officials of the Ministry of Finance (such as Guryev, Kashkarov, Kaufman, Witte himself), who actively participated in the process of public discussion of the issue in public debates, on the pages of periodicals, and in serious scientific publications. The same Kaufman (in fact, the “gray eminence” under Witt in matters of monometallism) notes:

“...With the formation of the appropriate legislative framework, the hidden devaluation of credit notes and the full provision of the issue of the latter, with the transformation of the State Bank into the central emission center of the country, subordinate only to the Ministry of Finance of Russia - under these conditions, the introduction of gold coin circulation will lead to an increase in indirect and expansion of direct taxation only due to the influx of foreign capital. ...An increase in government borrowing does not pose a danger if the borrowing is not in securities, but in metal and, at the same time, external borrowings are balanced by internal ones...

Typically, at that time, both supporters and opponents of the reform turned out to be right. For example, Alexander Dmitrievich Nechvolodov (1864 - 1938, Lieutenant General of the General Staff, rather known to his colleagues not as an economist, but as the head of counterintelligence of the Manchurian Army) noted:

“...From a comparison of the number of banknotes in the Empire with the amount of state debt and the state receipt for 1906, we see: a) all the money in Russia is almost five times less than state and government-guaranteed debts alone; b) the total amount of money in Russia is not enough even to fulfill the state expenditure list for 1906 alone. From an examination of our state monetary system, it is clear that for each new issue of banknotes, according to the Highest Decree of August 29, 1897, necessary to satisfy the urgent needs of monetary circulation, a corresponding increase in the supply of gold in the state is required, at least ruble for ruble. This same increase in the supply of gold can be achieved only in five ways: 1) gold, annually mined in Russia from the bowels of the earth; 2) by an influx of gold from abroad, as a result of the conclusion of a balance sheet in favor of Russia; 3) through external loans; 4) gold invested by foreigners in the country's industrial enterprises. 5) by conquering new markets for their exports and expanding old ones. Let us give explanations on these five points: 1. The amount of gold mined annually in Russia is worth from 40 to 46 million rubles. Thus, in this way the number of banknotes can be increased annually only by an insignificant amount. 2. The state’s balance sheet consists of the following data: a) from the conclusion of the trade balance; b) from the amount annually paid abroad in payment of interest and repayment on government and state-guaranteed securities located abroad; c) from amounts paid annually in the form of profits on foreign capital invested in enterprises; d) from amounts spent by Russians abroad; e) from amounts spent by the naval and military departments abroad.

From the review of the conclusion of the balance sheet, we see that it is constantly not in our favor, and over the five-year period 1897-1901. amounted to one billion two hundred twenty-one million seven hundred thousand rubles. 3. Loans. The significance of gold loans in state life comes down to the fact that interest and repayment are paid on them in gold, which is why the liability of gold is increasing more and more. 4. Attracting foreign capital to the fatherland. Attracting foreign capital to the state comes down to: the exploitation by these capitals of the country’s domestic wealth and labor, and then the export abroad of gold acquired in the country for the sale of production products. At the same time, the general welfare of the area where large capitalist industries arise necessarily decreases, according to the laws derived by Henry George in his “Progress and Poverty.” Thus, the results of the introduction of foreign capital into the state are as follows: a decrease in the general welfare in the surrounding area and the draining of gold from the country. By January 1, 1902, foreign capital invested in enterprises in Russia amounted to 1,043,977,000 rubles...”

S.Yu. Witte gave his proposals for reform to the emperor on February 4, 1895. They were approved. The decisive step towards the gold standard was the decree approved by the State Council and signed by Nicholas II on May 8, 1895. This document legalized the gold calculation and the use of gold in transactions:

“All written transactions permitted by law can be concluded for Russian gold coins... For such transactions, payment is made either in gold coins, in the amount determined by the transaction, or in government credit notes at the exchange rate for gold on the day of actual payment.”

In August 1896, the value of the gold coin in credit rubles was announced. Parity was established between paper banknotes and gold coins not based on their face value, but in accordance with the real exchange rate: credit ruble = 66 2/3 kopecks in gold. This established the basis of the new monetary system. This issue was discussed on February 2, 1897 in the financial committee chaired by the tsar himself. A decree “On the minting and release of gold coins into circulation” was signed. It was about the release into circulation of a gold imperial coin of 15 rubles. and semi-imperial at 7.5 rubles.

Imperial. They are often confused with ordinary Nikolaev chervonets, although these are completely different monetary units. You can distinguish it by the inscription “IMPERIAL” on the reverse, above the coat of arms. They were minted from 1895 to 1897 according to the “Alexandrovskaya foot” (weigh 12.9 grams each). The cost of one copy ranges from 2 to 5 thousand dollars, depending on condition. The “true imperial” was replaced by “intermediate” 15 rubles, which were minted for only one year (1897).

The May 1895 decree was followed by specific measures to introduce gold coins into circulation and into the sphere of transactions. The sale of gold coins was organized through State Bank institutions; It is allowed to accept gold coins for opening current interest-bearing accounts, paying government excise taxes, and for other payments through the cash desks of government agencies and private railways. Other measures were also taken, such as the issuance of special gold certificates (the so-called “deposit metal receipts”; their fate is a separate topic).

They were issued in exchange for gold and gold foreign currencies and were used for payments on a par with gold coins. In addition, gold coins began to be used to issue bank loans and pay salaries to employees of government and banking institutions. The rate was initially determined close to the exchange rate: 1894 -1895. – 14 rub. 80 kop. for a 10-ruble coin (imperial, 11.5135 g of pure gold), respectively 7 rubles. 40 kopecks for a 5-ruble coin (half-imperial). However, soon, for convenience, the rate was rounded up: one and a half credit rubles for one ruble of the denomination of a gold coin.

It was assumed that if the value of a gold imperial on which “10 rubles” was minted was declared equal to 15 rubles, then prices would increase by at least 1/3. However, this did not happen: domestic commodity prices did not react. This paradox of the Russian market of those years was explained by M.I. Tugan-Baranovsky (1865-1919):

“Prices in credit rubles have not changed at all, Russian economic life did not react at all to the decree. This was explained by the fact that prices on our domestic market were usually expressed not in gold, but in paper rubles and copper kopecks.”

In August 1897, standards for gold backing for the issue of banknotes were established: the issue of banknotes into circulation for 600 million rubles. should have been provided with a gold reserve of 300 million rubles, i.e. by 50%, and exceeding this limit is ruble for ruble, i.e. 100% collateral (1 imperial = 15 credit rubles).

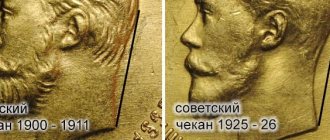

According to the catalog, very few chervonets were issued in 1911, fifty thousand pieces. But their actual number exceeds the declared one by several orders of magnitude even now, a century later, and in total they were counted up to 11 million copies. Most likely, although there is no direct evidence of this, the Bolsheviks continued to print the 1911 coins after the revolution. In 1925, the West staged a “golden blockade” on the USSR, within which the 1923 gold chervonets (“sower”) was not accepted in foreign trade payments. As a result, the gold intended for minting Soviet chervonets was used for royal coins, which were not subject to sanctions. Coins of Polish and Japanese pre-war minting are also known, identified by a number of characteristic features. There are persistent rumors among numismatists that coins are still being minted.

But there were also unpleasant side effects. By the Imperial Decree of August 29, 1897, the weight of the new ruble, previously artificially fixed since 1892 by external loans at the rate of 22/3 francs of gold, was determined to be 17,424 shares of pure gold. Simultaneously with the transition to a gold currency, Russia transferred to the new ruble, weighing 17,424 shares of gold, and all previous debt obligations concluded in silver rubles, weighing 4 spools and 21 shares of silver, according to the Manifesto of June 20, 1810. The same new gold ruble would henceforth be used to make payments on all previously concluded (in silver rubles) obligations, since with the introduction of the new law, silver was demonetized and remained only a bargaining chip. Those. the state debt on internal loans alone, which passed mostly into the hands of German bankers (the famous “Berlin scam”, which almost buried the reform), amounted in 1897 to 3,000,000,000 rubles, weighing every 4 spools 21 shares of silver, and therefore was expressed weighing 70,313 tons of silver. By transferring this debt to a new gold ruble of 17.424 shares of gold without reservation, Russia increased its weight in silver by 25,304 tons, but since in 1897 a ruble of 17.424 shares of gold corresponded not to a ruble of 4 spools of 21 shares of silver, but to almost seven spools of silver, then the government voluntarily increased the national debt by half, moreover, in obligations already for gold. Accordingly, there was an increase in the annual interest payment on this debt.

But nevertheless, new gold coins with denominations of 10 and 5 rubles. starting in 1898, they quickly came into circulation, banknotes were exchanged without obstacles. The share of gold coins in circulation in 1903 reached 52% of the country's total internal monetary circulation. This was facilitated by the constantly replenished gold reserves. So, if at the end of 1895 it was estimated at 964 million rubles, then at the end of 1913 - 2189 million rubles, and in tons, 746 and 1695 tons, respectively. In 1913, 95% of gold circulation consisted of new coins in denominations of 5 and 10 rubles, which began minting in November 1897 and December 1898, respectively. Minting of coins with a denomination of 15 rubles. and 7 rub. 50 kopecks from the beginning of 1899 ceased, and they quickly went out of circulation.

The volume of issues of new gold coins was quite impressive. According to A.V. Yurov and V.M. Gerasimov, 5-ruble gold coins for 1897-1911. 99.385 million pieces were produced, which amounted to 384.74 tons of pure gold. 10-ruble gold coins for 1898-1911. 42.259 million pieces were produced, which amounted to 327.18 tons of pure gold.

A clear difference between the chervonets stamps of different mints (8.6 g). Each contains 7.74 grams. 900 gold. On the obverse is a bust of Nicholas, framed by text, on the reverse is the small coat of arms of the Russian Empire, below it is the denomination and year of minting. Minted in large quantities, with the exception of 1906 and 1907. The edge indicates the contents and the mint in letters (less commonly, a “snake” edge).

The mints could not cope with the minting, and some of the coins were ordered abroad. One star on the edge of the coin means that this copy was minted in Paris, two – in Brussels, three – in Japan (after the revolution, the Japanese continued minting, but no longer indicating their authorship).

In Brussels, 50 gold kopecks (10 francs) were also minted; for the needs of Finland, coins in denominations of 20 and 10 marks were issued (the chervonets and pyaryok are repeated, but instead of the portrait of Nicholas there is an inscription indicating the denomination).

The decree of August 29, 1897 changed the procedure for issuing banknotes. Now the monopoly right of issue was assigned exclusively to the State Bank. Thus, for the first time, the State Bank was granted complete independence in regulating the money supply, and a barrier was put in place for the Ministry of Finance to cover the public debt through budget emissions, i.e. printing paper money. The issue of credit notes was made strictly dependent on the availability of gold reserves.

On November 14, 1897, another decree was issued, on the basis of which the inscriptions on credit notes were approved: “The State Bank exchanges credit notes for a gold coin without limiting the amount (1 ruble = 1/15 imperial, contains 17,424 shares of pure gold)”; “State banknotes are in circulation throughout the empire on a par with gold coins.”

The denomination of credit notes was set at 1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 and 500 rubles. After the reform of 1895-1897. new banknotes, which served as representatives of gold, gradually, until 1902, replaced the previous banknotes. For several years they circulated in parallel.

Gold coins quickly came into circulation. A large and constantly replenished metal fund provided the exchange of banknotes. They circulated as full and complete substitutes for gold. There were even times when gold predominated in cash circulation. The maximum was noted in 1903, when gold coins accounted for 52% of the country's total internal monetary circulation.

On the eve of the First World War, there were several dozen countries where banknotes were freely exchanged for gold. During the war, this exchange was stopped, and gold coins ceased to be minted. In Russia, the Law of July 27 (August 9), 1914 put an end to the existence of the gold ruble, opening the way for the dominance of fiat paper money, the issue of which has increased many times over. The Paris World Monetary System also ceased to exist.

Is it possible to return to the gold standard system?

Backing the ruble with gold can be the main key to solving many domestic and international problems, but it is important to remember that this is not a panacea or protection against inflation.

Some experts call such resuscitation a utopia and call for considering the option of cryptocurrency.

The volume of world and Russian trade is so large that it is impossible to provide it with gold. But, according to many signs, one of which is the rapid increase in gold reserves, the leadership of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation and the president are planning to set a course for a return to the gold standard. Pavel Maslovsky, an entrepreneur and politician, expressed the idea “that this is inevitable.”

Options for backing the ruble with gold

The current financial system is not sustainable in the long term. Sooner or later there will be a collapse. Therefore, the global financial elite is looking for ways to solve the brewing crisis. One such option is bitcoins.

A return to a solid backing of the ruble in gold is possible in several options:

- World standard. Alan Greenspan, head of the US Federal Reserve, is an ardent supporter of returning the US to the gold standard. Since the dollar continues to be the world currency, he believes that without a return to the solid backing of the United States, no country will be able to back its currency with gold.

- Gold and foreign exchange relations between a group of countries, for example, Russia - China.

- Transition to providing gold only for the Russian Federation.

Gold coins of Nicholas II 1897-1898.

The highest personal decree 13611 of January 3, 1897, given to the Minister of Finance, provided for the minting of gold coins according to old standards, but indicating a new denomination. That is, this document regulated the minting and putting into circulation of coins in denominations of 7.5 and 15 rubles. During the reform, the St. Petersburg Mint was so busy minting gold coins that the order for part of the circulation of money from high-grade silver (1 ruble, 25 and 50 kopecks) was transferred to Brussels and Paris. During this period, the mint did not deal with copper money at all. They are designated S.P.B. minted first in Birmingham and then at the Rosencrantz factory. The design of new denominations continued to follow the standards laid down from the beginning of the reign of Nicholas II. His left-facing profile occupies most of the obverse, surrounded by an abbreviated title, divided in two: B.M. NICHOLAS II EMPEROR - AND AUTOCRET OF ALL RUSSIA... On the reverse was minted the State Emblem in the form of a double-headed eagle crowned with crowns, denomination and year of issue. A sequence of rounded teeth was minted along the edge on both sides. The famous medalist Anton Fedorovich Vasyutinsky worked on the obverse stamps. The reverse stamps were designed by Avenir Girshevich Grilikhes (numismatists express doubts only regarding the five-ruble note, where his sign was not found).

The new imperial had difficulty going through the stages of approving the imperial portrait. Suffice it to say that there are two types of probes, distinguished by the size of the emperor's head (small and large). A common feature of trial imperials was that the last four letters of the title extend beyond the neckline (ROSS). These portraits did not receive the approval of Nicholas II. On mass coinage, the size of the emperor's head also varies, but collectors divide the coins into two types according to the number of title letters extending beyond the neck edge (OSS and SS). During 1897, the mint minted 11,900,033 pieces of both varieties of imperial. They did not continue minting further. The weight of the precious metal is fixed on the edge in the spool system of measures (PURE GOLD 2 GOLD 69.36 LOVES). There is also the sign of the mintzmeister (AG) - the initials of Apollo Grashof, enclosed in parentheses and separated by a large dot. Despite the fairly large circulation, the imperial is very popular in collecting circles and is sold for much more than the value of the gold contained in it. To accept government payments into account, the weight of the coin was checked. If it was below three spools and one share (12.8417 grams), the specimen was rejected.

The unusual denomination of 7 rubles 50 kopecks, corresponding to the gold five-ruble note of the times of Alexander III, was also minted in accordance with Decree 13611. The gold content is also indicated on the edge (PURE GOLD 1 ZOLOTNIK 34.68 HALES) along with the sign of the mintsmeister (AG). In total, the St. Petersburg Mint produced 16,829,000 copies of the semi-imperial. No varieties of the coin have been identified, and in catalogs it is listed in one position. Although some collectors divide semi-imperials according to the type of portrait of Nicholas II into flat chasing and convex chasing. Minting was also carried out for only one year. Similar coins with other dates are unknown. For payments, coins with a total weight of at least one spool and forty-eight shares (6.3986 grams) were accepted. All characteristics of the imperial and semi-imperial, including the lower permissible weight limit, were included in the Coin Regulations in 1899.

As stated in Executive Order 13611: Due to its importance and complexity, this matter may still require lengthy discussion. - that’s what happened. It is not known whose dissatisfaction or rejection the new denominations caused, but during 1897 proposals were made to return to coins of the usual denomination, albeit with a lower gold content. The result of the discussions was Decree 14632 of November 14, which began with the words: To facilitate payments with gold coins, We recognized it as a good idea to approve your proposal, considered in the Special Committee, on the minting and release into circulation, in addition to the imperial and semi-imperial coins, of a five-ruble gold coin of one denomination third part of the imperial. The St. Petersburg Mint immediately began minting a new denomination and managed to produce 5,372,000 five-ruble coins with the date 1897. Here they decided to deviate from previous standards and not place the gold content of the coin on the edge, limiting themselves to an ornament from a sequence of segments bent at right angles, among which they placed mintmaster sign - (AG). However, a small part of the circulation did not receive a rim design, and now these coins are considered real numismatic rarities. The weight limit below which a coin could not be used for payments was set to one spool (4.2658 grams). The peak production of five-ruble notes occurred in the next three years: 1898 52 378 008 units, 1899 20 400 004 units and 1900 31 077 013 units. In fact, even more coins with these dates were minted, since in the mid-1920s the Soviet government issued an additional edition with old stamps for international payments. The rarest dates are 1906 (10 pieces) and 1907 (109 pieces). The circulation of 1909 is unknown, but it is clearly larger than that of the two subsequent years.

The release of the ten-ruble coin took the longest time. Its appearance was regulated by Decree 16199 of December 11, 1898. Like the five-ruble coin, this coin became the most popular of the line that appeared during the Witte reform. The gold content along with the mintmaster's mark is indicated on the edge (PURE GOLD 1 ZOLOTNIK 78.24 SHARE). The lower acceptable limit for ten rubles as a means of calculation is two spools and six tenths of a share (8.5582 grams). In the first year of minting, only 200,000 ten-ruble notes were issued. The largest circulation (27,600,013 pieces) occurred in 1899. The rarest gold tens coins of 1906 (only 10 copies). Dozens with the date 1911 should also be rare (according to documents there are only 50,011 of them). However, the Soviet minting of tsarist gold significantly increased their number. Before the revolution, no one called gold tens chervonets. The nickname stuck to them after the minting of the Soviet chervonets gold coin of the RSFSR with similar parameters. In the first years of Soviet power, royal ten-ruble notes could be used to pay as hard currency. During the period of unstable ruble, dollars or euros now play approximately the same role.

However, it should be noted that ten-ruble gold coins were still minted in 1897. They had a double denomination of Imperial 10 rubles in gold. But they were issued according to the Rules on the Coin System of 1885, that is, they represented the imperial of the old standard. This is a donative coin that was given at the royal court as a particularly valuable gift. Their circulation is extremely small. For example, in 1896, 125 such imperials were produced. The circulation for 1897 has not been established. They could not be circulating coins.

What will happen if the ruble is tied to a precious metal: critics’ opinions

Experts in their comments on the return to the previous system sometimes express directly opposite opinions. Some advocate for reinforcing the Russian ruble with gold - fortunately there are reserves and deposits. Others appeal with hard facts and refute the very possibility of such a scenario.

Anton Tabakh, a commentator for Forbes magazine, believes:

“The need for self-restraint will most likely be the main factor preventing the transition to the gold ruble, which, quite possibly, would be useful for the population and business.”

The modern economic encyclopedia contains data that pegging the ruble to gold will ultimately lead to a shortage and an increase in the price of money itself as a fact due to the limited possibilities of their issue, which in turn will lead to a decrease in production and an increase in unemployment. There will be an abundance of goods, but there will be nothing to buy them with.

According to the vice-president of Z.M.D. A. Vyazovsky, “gold is an excellent investment instrument, but a return to the old days, when it served as a means of payment, is hardly possible.”

Progress of reform

Preparations for the reform began in the 1880s and were caused by the instability of the monetary system. In February 1895, Finance Minister Sergei Witte presented a report to Emperor Nicholas II on the need to introduce gold circulation. Witte decided to introduce the gold standard adopted in England, rather than the gold-silver standard that was formally in force in France.

By the law of May 8, 1895, it was allowed to conclude transactions in gold, at the same time all offices and branches of the State Bank were given the right to buy gold coins, and 8 offices and 25 branches also made payments with this coin. In June 1895, the State Bank was allowed to accept gold coins into a current account (private St. Petersburg banks followed this example); in November 1895, gold coins were allowed to be accepted by the cash registers of all government agencies and state-owned railways. In December 1895, the rate of credit notes was established at 7.40 rubles for a gold semi-imperial with a face value of 5 rubles (since 1896 - 7.50 rubles).

By 1897, the State Bank increased its gold cash from 300 million to 1095 million rubles, which almost corresponded to the amount of banknotes in circulation (1121 million rubles).

On August 29, 1897, a decree was issued on the issuing operations of the State Bank, which received the right to issue credit notes, freely and without restrictions exchangeable for gold.